When we hear the phrase the “Black Wall Street”, we automatically think of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. More than just a thriving community, this neighborhood was a Black utopia that flourished in spite of the oppressive grip of segregation; yet, any mention of this community simultaneously invokes two visceral emotions – pride in its achievements and anger at its unjust destruction.

This community was regarded as one of the most commercially successful and affluent African American communities in the United States, with Greenwood Avenue - “the Black Wall Street” - forming the bourgeoning epicenter of African American culture and business. Against the backdrop of a Jim Crow era, this community became self-sufficient, with its own grocery stores, hotels, movie theaters, and offices for doctors, lawyers and dentists, as well as its own school system, hospital and taxi service.

Between May 31 and June 1, 1921, what is considered to be one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history, unfolded in Tulsa. Black residents of Greenwood were attacked by a white mob, who destroyed virtually all of the community. More than 35 square blocks of a vibrant community were demolished, as many as 300 people were killed, over 1,200 homes and businesses reduced to ash and nearly 10,000 people were left homeless. What took years to build - Black success against all odds - took only two days to come crashing down.

Although this remains one of the most widely recognized “Black Wall Streets”, a number of others emerged across the United States in response to Jim Crow segregation, driven by the need to create insular economies and self-sufficient communities. Their contributions and achievements, though lesser-known, reflect the same resilience and tenacity that gave birth to the Greenwood District.

Seventh Street – West Oakland, California

In the early 1900s, the Great Migration saw a large number of African Americans migrating from the South in an attempt to escape racial discrimination and in search of better opportunities. A result of this was the emergence of Seventh Street, West Oakland, which became a vibrant center for Black entrepreneurship and culture. With a number of Black-owned businesses, including restaurants, hotels and some of the best-known jazz clubs, such as Esther’s Orbit Room, West Oakland served as a cultural haven for African Americans.

Hayti District – Durham, North Carolina

Between the 1880s and 1940s, the Hayti District, located in Durham, North Carolina, became one of the most successful Black communities in the United States, known for its thriving economic and cultural life. Home to over 200 Black-owned businesses, including the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, the Hayti District, established in the years following the Civil War, had its own schools, barbershops, hotels, churches and hospital (the Lincoln Hospital).

U Street – Washington, D.C.

Dubbed the “Black Broadway”, U Street was regarded an economic, cultural, social and spiritual hub for African Americans during the Jim Crow era. Considered “a city within a city”, U Street was home to over 200 Black-owned businesses, funded with loans from the city’s oldest black-owned bank, and which were patronized solely by African Americans. Still considered to be Washington’s “cultural center”, some shops, such as Ben’s Chili Bowl, which opened for business in 1958, continue to exist today.

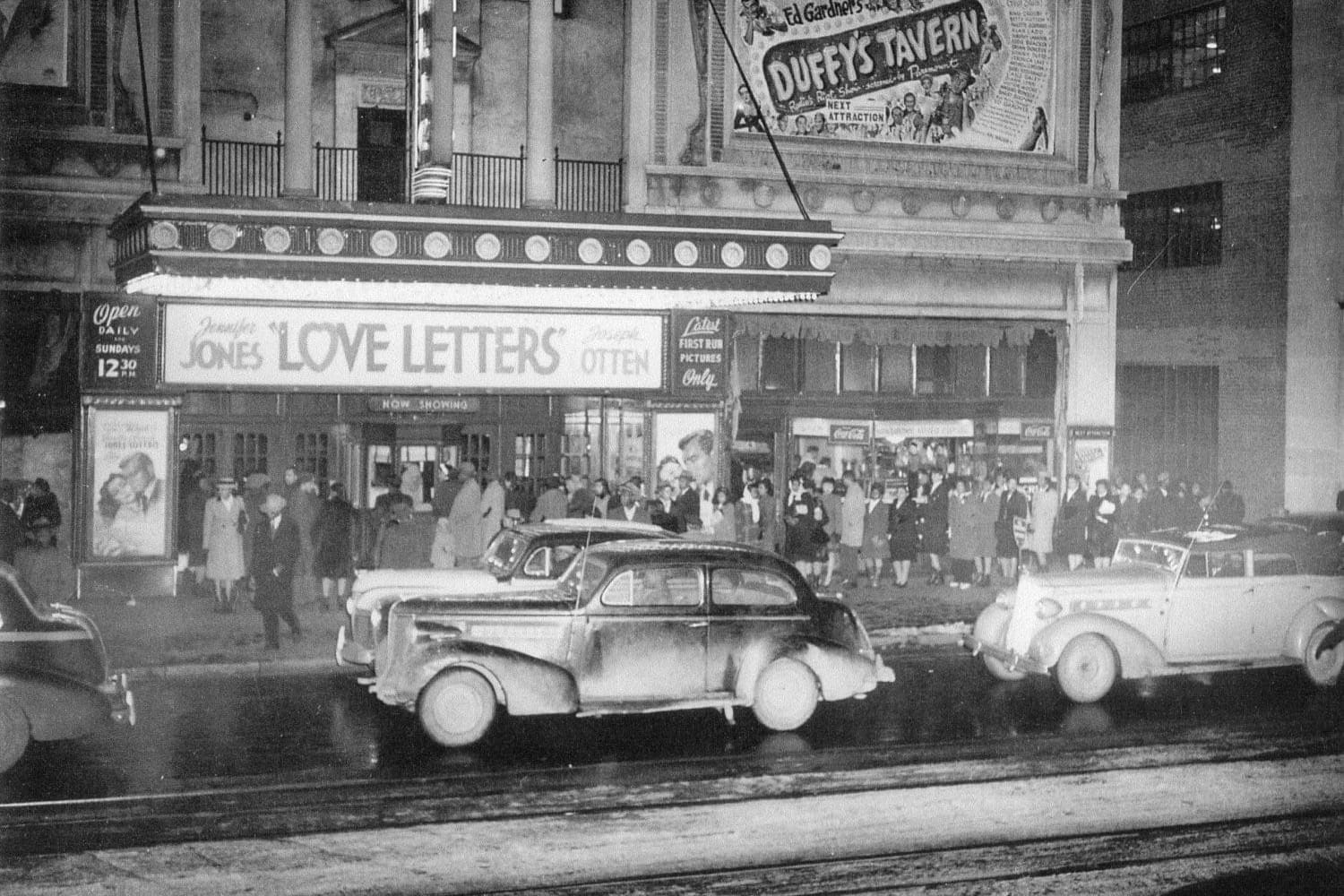

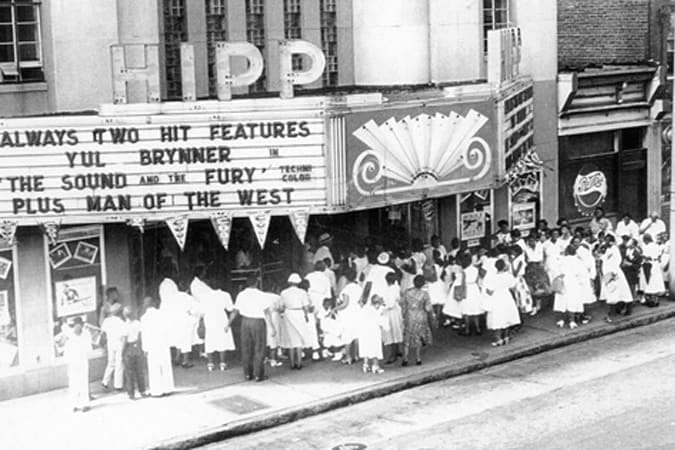

Fourth Avenue District – Birmingham, Alabama

In the early-to mid-20th century, the Fourth Avenue District, Birmingham, Alabama, emerged as a center for Black-owned businesses, including restaurants, motels, cafes, theaters and more. With a range of commercial activity that supported the local economy, the community also became home to a number of critical community institutions, including the Alabama Penny Savings Bank building, and the 16th Street Baptist Church, which operated as a center for social and community gatherings and later became a target of a racially motivated bombing in 1963 that killed four young black girls.

Jackson Ward – Richmond, Virginia

In the aftermath of the American Civil War in the 1860s, Jackson Ward in Richmond, Virginia, experienced an influx of African Americans, many of whom migrated in the era of the “Great Migration”. It was eventually nicknamed the “Harlem of the South”, as it served as an early space for Black entrepreneurship, creativity and culture. Home to more than 100 Black-owned businesses, including insurance companies, law offices and pharmacies, Jackson Ward saw a number of African Americans prospering in professions such as medicine and law, alongside a growing home-owning, Black middle class. It is home to the US’s first Black female bank president, Maggie Lena Walker, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, pioneer tap dancer and singer.